Masking for Representation Learning in Vision

Masked-image modeling (MIM) is about inpainting; that is, covering parts of an image and then trying to recover what was hidden from what is left. Recently, it has led to state-of-the-art representation learning in images1. In this blog, I will dive into why masked images deliver such a powerful learning signal, think about what may constitute a good mask, and discuss my recent paper (ADIOS) which attempts to learn good masks for representation learning. But let’s start with some motivation.

Masking and the Brain

Have you ever covered an object you saw with your hand and tried to imagine what the covered part looks like? If not, why not give it a try? You may be unable to draw or paint it since that requires considerable skill. You may not even be able to see it clearly in your mind’s eye. Yet, you know what it is or what it can be used for—in other words, you have a good representation of it. Getting such representations is, roughly, the goal behind masked-image modeling (MIM).

Reconstructing the hidden part from the visible parts is called image inpainting, or more generally, missing-data imputation.2 While MIM models are usually trained via image inpainting, we will see later on that reconstruction is not always necessary for learning good represetations. But actually, this is what your brain is doing all the time!

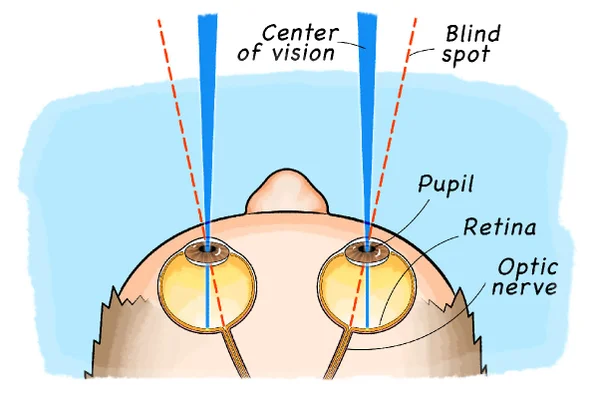

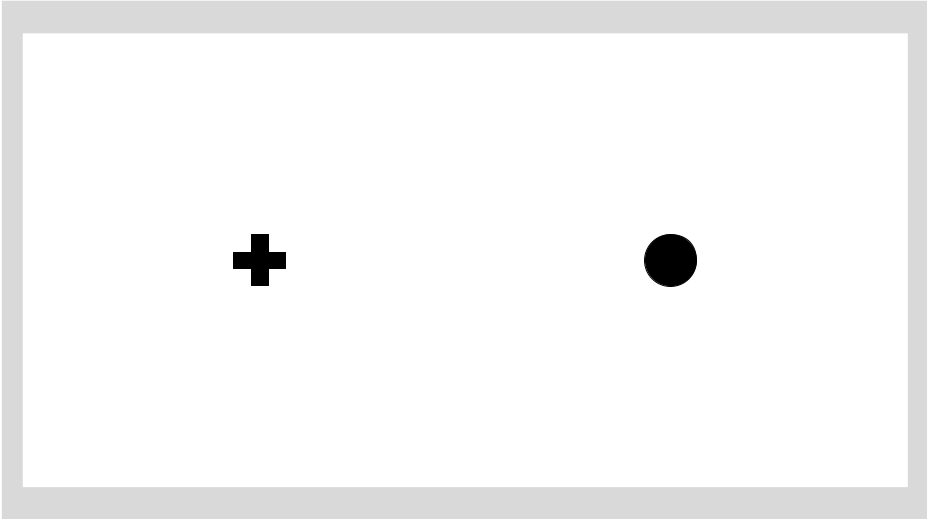

Each of your eyes has a visual blind spot; as shown in the figure above. It’s roughly in the middle vertically, and slightly off-center to the outside for each eye. You don’t see anything there because it’s the place where the optic nerve connects to the eye, leaving no place for photoreceptors. And yet, you are unaware that any information is missing: you seem to see what is hidden. See for yourself!

If you followed the test in in Fig. 2, you know that the blind spot exist—and that we should be experiencing its effects whenever we use our eyes to observe the world. How come this is not so? This is where the magic of unconscious perception comes in: our brain inpaints the “blinded” area for us, to the point where we don’t even know that blind spots exist! This may be based on what is around that area but also using the view from the other eye (novel-view synthesis3) and what the brain is expecting to see in a given context.

I expect that the ability to inpaint in the brain is not innate and that the brain has to learn how to do it. If this is the case, is this something that guides the brain in learning good visual representations? Given the very impressive representation learning results of recent MIM models, I wouldn’t be surprised if it was the case.

It is also interesting that even though the brain is really good at inpainting (people don’t usually know about their blind spots) or imagining (e.g., vivid dreams), this is not a capability we control consciously. Think about that object you covered: you know what it is, but you probably cannot project a pixel-perfect rendering in your mind. This is rarely problematic, because conscious reasoning relies on high-level abstractions, not pixel-level detail. Since the representations we try to learn are usually used in such higher-level reasoning tasks, perhaps reconstruction is not the right way to go?

We will come back to this question later. For now, we will look at a few methods that do involve reconstruction.

BERT or Why Inpaint for Representation Learning?

Because it works—as shown by BERT of Devlin et al. in 2018. BERT is a large transformer trained to fill in missing words in natural language sentences based on the available words. Why is this useful? Because words typically represent concrete objects or abstract entities, their properties, and relations between them. To predict which word makes sense in the presence of other words, is to analyze what objects and with what properties are represented in that sentence, and what the relations between them are. A model that learns to do that learns many truths about the world4.

So why not do this for vision? You can, but it is not as straightforward as pushing a masked image through a CNN. If that’s what you do, you get the Context Encoder (CE) by Pathak et al., which came out in 2016, two years before BERT. CE used a small CNN (AlexNet-based) in an encoder-decoder setup. The images are either masked by a single large-ish rectangle, multiple smaller rectangles, or the ground-truth segmentation mask from another image. While the learned representations are ok, their performance is far behind supervised models of the time, even when fine-tuned.

Why? First, there is an architectural issue. CNNs are great at correlating pixels. But filling-in missing words is about reasoning about objects, parts, properties, and relations. This is what transformers are really good at, but at the time, there was no good way of using transformers for vision. Second, there is a representation issue. Words in natural language are fundamentally different from pixels in images. So masking just a few random rectangles is unlikely to bear similar results to masking words.

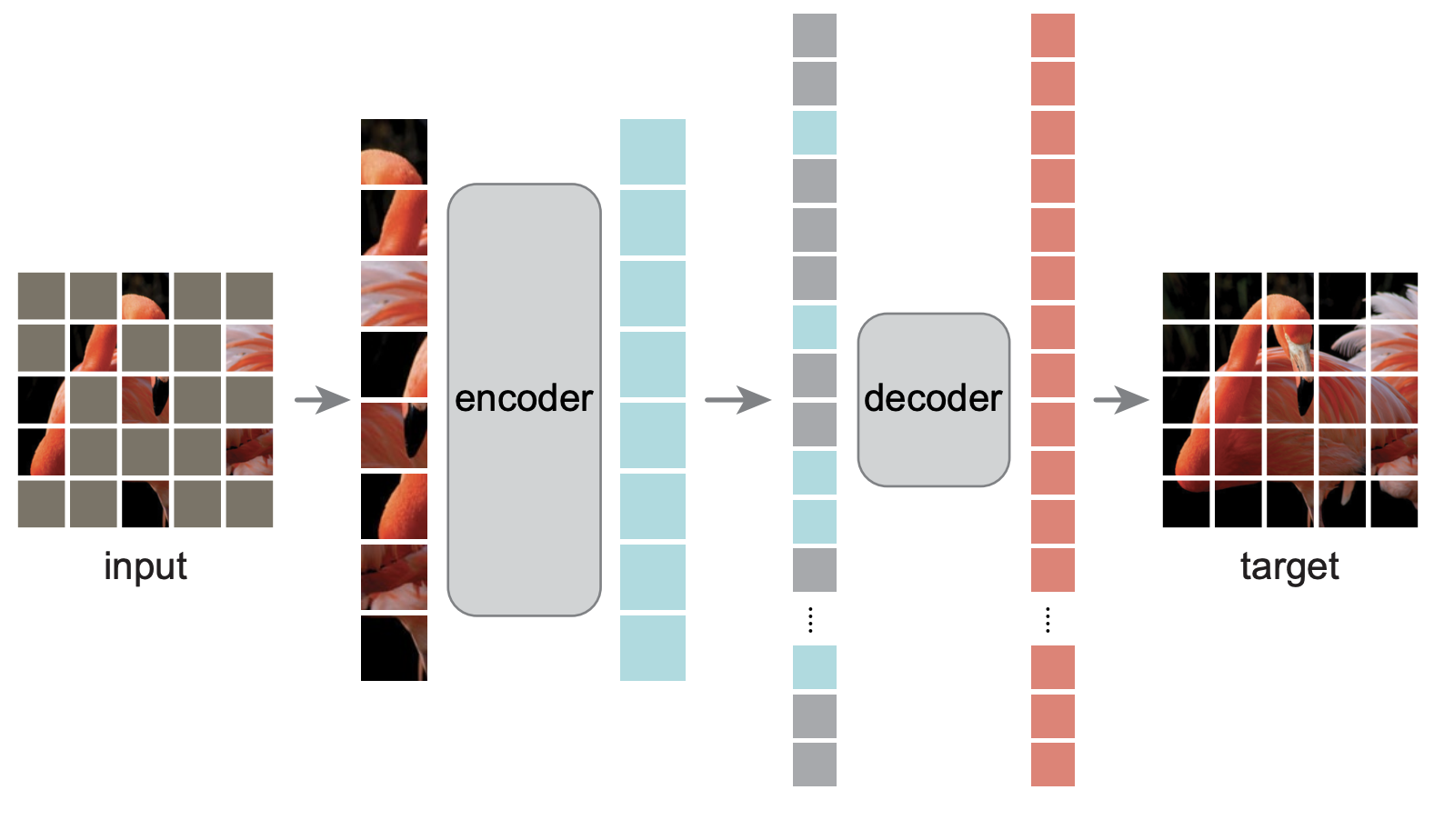

It was the Masked Autoencoder (MAE) by He et al. that finally proved that image inpainting can lead to state-of-the-art representations for images. Coming five years after CE, it brought in recent advances. The encoder is a large vision transformer (ViT, Dosovitskiy et al.). The image is split into a rectangular grid, as in ViT, and a number of grid elements are masked. This paper provides two insights:

- The representation quality improves with the fraction of the image masked (up to a point).

- Instead of feeding an image with masked parts to the encoder, it is better to just not use the masked parts as an input5. This is easy to do for an image-divided-into-patches and a transformer like in ViT, but next to impossible for a CNN.

MAE masks consist of small, randomly-scattered rectangles corresponding to the ViT image patches. They cover 75% of the image, which is significantly more than in CE6.

Why is this important? Because masking a large proportion of the image makes it more likely to mask visual words.

What is a Visual Word?

A word typically represents an entity, its property, or a relation between entities. A pixel represents a color. A visual word is a group of pixels, but it is not a random group. Rather, it’s a group of pixels that represents something meaningful like an object, but also a property or a relation.7. Imagine a man wearing a red jacket.

- To mask “red”, we need to occlude most of a jacket, perhaps leaving its outline.

- To mask “jacket” without masking its color, we can mask its outline but leave a pixel here or there.

- To mask the fact that someone is wearing the jacket, we need to mask out a person while leaving fragments of the jacket.

Such groupings are far from random and are extremely unlikely to occur with random masks. Masking a significant area of the image, like in MAE, makes it easier to occlude visual words (whole entities, say). As the paper shows, such masks are also better for representation learning. Still, masking properties or relations remains difficult under that scheme.

Finding Visual Words

Let’s assume that, for representation learning, masking single words in natural language sentences is the best thing to do. How do we get such visual-word masks for images?

We would need to identify image regions that are similar in meaning to words. Object bounding boxes or segmentation masks would be a good choice if not for two issues. First, they usually cover objects, with no masks or boxes describing relations between objects or parts thereof8. Second, they are human-generated, which defeats the purpose of unsupervised learning. Let’s explore alternatives.

Visual Words from Before Deep-Learning

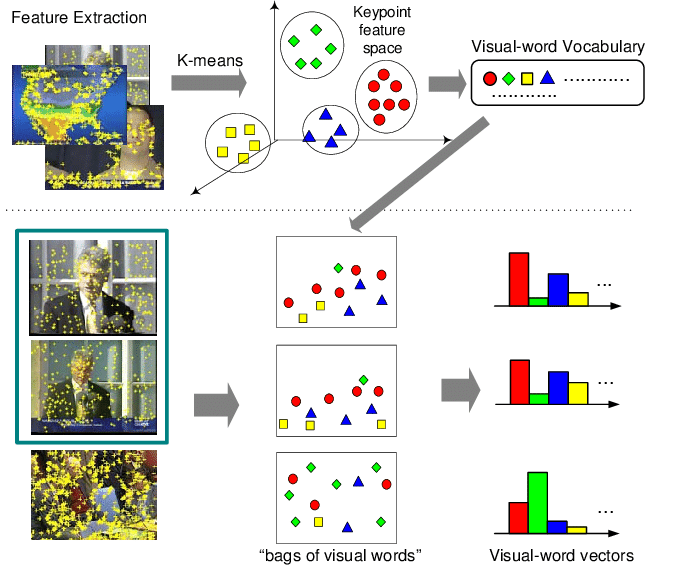

The concept of a visual word has been studied before in the pre-deep-learning era. Inspired by bag-of-words classifiers for natural language (e.g., an SVM operating on word histograms, the so-called bags of words), people constructed visual bag-of-words classifiers.

Dictionaries of visual words were built by running a SIFT or SURF keypoint detector on a dataset of images, describing these keypoints with relevant descriptors (SIFT, SURF, HOG), and then clustering them. The cluster centroids represented a new visual grammar. A new image could be classified by creating a histogram of such visual words and feeding it into an SVM, say. A visual word like that could correspond to an eye or a car wheel. While I haven’t tried it, it would be interesting to adapt this paradigm for MIM.

Learning Visual Words

The modern alternative is to learn what a visual word is. To understand how visual words can be learned, let’s think about what categories of masks we can expect. We can do it by looking at some air balloons.

If you occlude a piece of the background, in this case, an empty sky, you can easily fill that piece in. If you hide a random part of an object, you can easily imagine that hidden part—its contents are largely defined by the visible parts of the object. If you hide a semantically-meaningful piece of an object, e.g., the balloon part of an air balloon, you have a somewhat harder task. Now you know that there should be a balloon because you can see a basket. Based on the context, you know that it probably belongs under a balloon. But the balloon can have a range of sizes and can be painted in many different ways, which increases the difficulty of the task. Finally, you can hide the whole object. This is virtually indistinguishable from hiding a piece of the background. You will have a hard time figuring out what the object was or if there was an object at all. The only way to do this is to check if it would make sense for any particular object to be there, given the visible surroundings.

This gradation of difficulty in different masking scenarios stems from the fact that some pixels are predictable9 from each other, while others are not. For a longer discussion, see section 4.1.1. of Greff et al, “On the Binding Problem in Artificial Neural Networks”. For now:

- Pixels belonging to an object are strongly correlated with each other.

- Pixels belonging to different objects or an object and the background are not correlated or are correlated only very weakly10.

By now, this is a widely-accepted view. I would go a step further and say that pixels representing a relation7 (e.g., two objects that often appear together), or a property, are also strongly correlated; therefore, they are possible to infer from a partial observation.

The above intuition can be formalized as a training objective.

This is exactly what we do in Shi et al., “Adversarial Masking for Self-Supervised Learning”, ICML 2022 (code).

Adversarial Inference-Occlusion Self-supervision (ADIOS)

ADIOS is a reconstruction-free MIM model that learns to mask in an adversarial fashion.

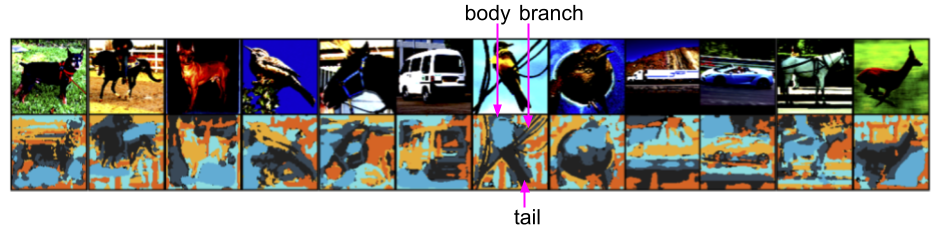

Imagine a setup where you try to inpaint an image with some parts occluded. To get the mask, we instantiate a masking model whose job is to make inpainting as difficult as possible, subject to some constraints (see below). The result? You get masks that seem to hide objects or their parts. You also get better representation learning results than with using MAE’s masks11.

What constrains masking whole objects, or the entire image for that matter? First, we predict several masks while making sure that each pixel is masked only once. Second, we penalize the masks so that they cannot be all black or all white. These two constraints mean that none of the predicted masks can cover the whole image and that the image must be partitioned between all masks. Third, there are built-in inductive biases in the form of the masking net architecture (Convolutional UNet pays more attention to texture than semantics) and the encoder architecture (ViT seems to result in masks that look more semantically-meaningful than when a ResNet is used).

Recall that MIM models are trained by reconstructing occluded images, similar to how the brain inpaints the visual blind spot. But since we are not interested in pixel-perfect detail but rather high-level, conscious-like reasoning abilities, we may be able to get away without reconstruction. That’s why we resort to reconstruction-free representation learning (RFL)12.

ADIOS applies to any siamese-style representation learning algorithm (contrastive or otherwise) where the training is done by minimizing some distance between representations. Here we compare a generic algorithm with its ADIOS-augmented version. The ADIOS-specific parts are highlighted in green.

- Take an image x.

- Create two views of that image, a and b.

- skip

- Encode the views with a neural net with parameters θ to get two representations z_a and z_b.

- Compute a loss L(z_a, z_b).

- Update the parameters of the neural net(s) by minimising that loss with respect to θ.

- Take an image x.

- Create two views of that image, a and b.

- Predict a mask m = mask(b) with a neural net with parameters φ. Apply that mask to b.

- Encode the views with a neural net with parameters θ to get two representations z_a and z_b.

- Compute a loss L(z_a, z_b).

- Update the parameters of the neural net(s) by minimising that loss with respect to θ and maximising with respect to φ.

In ADIOS, we want one of the image views, say b, to be masked. The mask m = mask(b) is conditioned on the image and is predicted by another neural net with parameters \(\phi\). We get a masked image \(b^m = b \circ m\) by applying the mask to the image (via element-wise multiplication \(\circ\)), and extract representation \(z_b^m\). At the end, in addition to updating the encoder’s parameters, we also update the parameters of the masking neural net by maximizing the loss L with respect to \(\phi\).

That’s it! It’s simple, isn’t it? A cool thing is that is works with many different RFL objectives (we tried BYOL, SimCLR, and SimSiam), and it improves representation learning performance on every dataset and task we tried. Additionally, ADIOS improves robustness to non-adversarial attacks (e.g., changing the background behind an object), presumably due to decreasing sensitivity to spurious correlations (these are often masked separately from the object due to the correlation structure discussed above).

How Does Masking Apply to Reconstruction-Free Learning (RFL)?

RFL minimizes the distance between representations extracted from two views of the same image. That distance is minimized when the encoders are invariant to the transformations applied to the source image. Here is a simple example: if we use a color image and a grayscale version of that same image, we will get a representation that encodes the content (e.g., objects) and even brightness, but not the hue. Hence, we say, the representation is invariant to hue variations. See Fabian Fuchs’ blog for a longer discussion of equivariance and invariance.

Using a masked image as one of the views means that we want a representation that is invariant to masking. There are two ways to do this:

- Ignore any region that can be masked.

- If a region is masked, try to predict what was there before masking.

Option 1. means encoding no information (representation collapse) and is usually incompatible with any good learning objective. That leaves option 2. and forces the model to reason about occluded parts. The masking model is trying to make 2. more difficult. Hence it learns to mask strongly-correlated groups of pixels, which often correspond to semantically-meaningful object parts, but do not necessarily correspond to objects—as discussed.

Summary

That’s it! If you got this far, you learned about visual blind spots and (hopefully) found your own, which gives you a pretty good idea how much inpainting our brains do. This is similar to masking and then inpainting images, which leads to some state-of-the-art representation learning. You also know that semantically-meaningful masks lead to even stronger results than random masks, and you’ve seen a couple of ways to get such masks.

So is pixel-level reconstruction the right way to go if you want to get good representations? While we do not have a definitive answer, we show through ADIOS that reconstructions are not always necessary, and that the motivation behind reconstruction-based MIM models does extend to the reconstruction-free setting.

If you’re interested in more details behind ADIOS, have a look at the paper, and play with the code!

Here are a few things you could try:

- Figure out how to learn masks for MAE without processing the whole image with the encoder, and perhaps with higher granularity than afforded by masking individual patches.

- Experiment with stronger inductive biases for the masking model like slot-attention or GENESIS.

Further reading:

- SemMAE, which came out a few days ago, provides an alternative way of learning visual-word-like masks by using arg-maxed attention from another transformer.

- “On the Binding Problem in Artificial Neural Networks” from Klaus Greff and Sjoerd van Steenkiste discusses at length what objects are and how to represent them in neural networks.

Acknowledgements

Huge thanks to Yuge Shi for doing most of the work behind the ADIOS paper. I would also like to thank Yuge Shi, Sandy Huang, Fabian Fuchs, Klaus Greff, and Sjoerd van Steenkiste for proofreading and providing helpful suggestions for this blog.

Footnotes

-

MAE, BEiT, SemMAE as well as our paper ADIOS, which is discussed further below. ↩

-

“Variational Autoencoder with Arbitrary Conditioning” by Ivanov et al. was the first paper that got me thinking about image inpainting. ↩

-

Sajjadi et al. show that novel-view synthesis helps to learn object segmentation in an unsupervised setting. A long shot and a topic for another blog, but I wonder if the blind-spot inpainting in the brain could help with object perception. ↩

-

I know this may sound unscientific and overly hyped. It is. I like this rhetoric, though. ↩

-

If the masked patches are used as input, the model has to learn to ignore them. Since MAE masks 75% of the image, there is probably no benefit to representing which areas of the image are masked (they are represented implicitly, since there is no contribution from the masked patches). By asking the model to learn-to-ignore, we are wasting model capacity while also risking falling into a local minimum where the masked patches are not totally ignored. Note that in transformers we can hardcode to ignore masked patches while feeding them as input, but this is more computationally-expensive and requires changing the implementation; for a convnet this may be impossible. ↩

-

It is unclear what the impact of such scattered masks is. It might force the model to reason about multiple things in every image. It may also reduce the variance of the gradients because total occlusion of a certain object is less likely with such scattered masks. ↩

-

Sjoerd van Steenkiste pointed out that there may be no such thing as a pixel representing a relation, e.g., no group of pixels may represent “heavier than” or even “bigger than”. While I agree, I’d like to note that masking pixels can obscure such relations. In case of “bigger than”, a mask can occlude a part of an object making its size difficult to determine. This may be useful for representation learning. ↩ ↩2

-

The latter could be perhaps circumvented by editing ground-truth masks, e.g., taking a union of two object masks, diluting or eroding masks, etc. ↩

-

See that, according to above, the background behaves just like a big object behind the objects in the foreground. ↩

-

The caveat is that using such learned masks requires feeding the whole image into the encoder. This results in a significantly increased computation cost for MAE and might not be practical. ↩

-

While I don’t like creating acronyms, I find that the currently available options are somewhat lacking. All representation learning algorithms we care about are unsupervised (self-supervised is unsupervised). The ones that require image reconstruction (inpainting, e.g., MAE) use one encoder and one decoder. The ones that do not require reconstruction (e.g., SimCLR) use two encoders and no decoder. The latter were called contrastive (but some methods do not use negative examples) and later self-supervised learning (SSL; but this is too broad since MAE is also SSL). Hence, I adopt “reconstruction-free learning (RFL)” to distinguish these two paradigms. An alternative that focuses on architecture would be “Siamese-Style Learning”—maybe this is better because it uses the same acronym? ↩